A Part of Everything

Are you a branded house or a house of brands?

Do your programs need a brand of their own, or should they be sub-branded under your own?

Brand architecture is the complicated process of dealing with the fact that your brand is a part of everything. When we talk about brand architecture, we're not talking about design, messaging, or an org chart. We're talking about all of it. In this newsletter, I'll share a few examples created by us here at Matchbook that may help illuminate how to think about brand architecture. We'll start with a few examples and then talk about how to bring ideas from each of them together.

Unique Identities

We’ll start with a school system. When we did the branding for Hamilton Southeastern Schools, their goal was to build a system that was modern and easy for internal communications teams to use but also looked like each logo belonged together when seen on shared documents or websites.

At the same time, each school was part of a different subcommunity with its own identity and a desire for that to be reflected in its image, specifically regarding athletics.

We created a system that introduced a professional parent brand, and for each school logo, we incorporated it cleanly into the base of each mascot image to build an organization-wide brand standard across a group of unique smaller brands.

Programs and Target Audiences

Most of the time, brand architecture is much deeper than logos, even when a logo may be a tool to tie those brands together in the mind of your audience. This is where brand nomenclature, such as the naming structure of services and programs, is an important consideration. Sometimes, services and products are simply options offered to your customers. In other cases, these options may be meant for different customers altogether.

For the engineering and construction company P2S, we developed a brand system built around a single logo, which may connect to different audiences or address concerns that are experienced at different times. Following the logo, each brand connects to themes that identify the kinds of photography and messaging that fit best. In this example, we use small variations in color and sub-brand names to signal the differences between brands within the same family.

Messaging Structure

Another form of brand architecture is the structure of messaging, all inside of the same brand and targeted at the same audience. Developing the standards of your foundational messaging comes from capturing statements that address different key points important to a customer. Often, we think of these as building blocks that reference individual ideas but, together, build a single brand story.

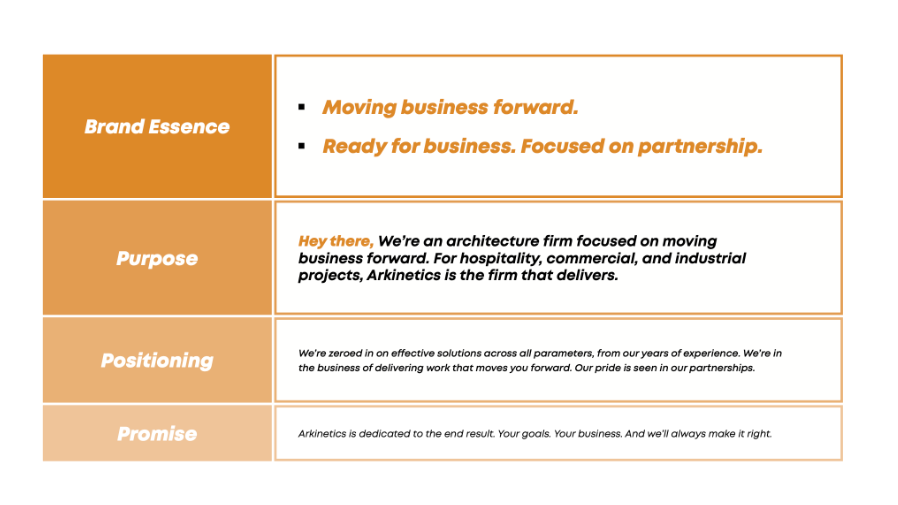

For Arkinetics, we developed baseline messaging to define the style of the Arkinetics brand voice while establishing key verbiage to describe the value of working with the firm. An expansion of this example goes deeper and addresses service lines, audience-specific messages, and additional nomenclature.

Decision Trees

Brands are like containers for ideas. They help companies communicate to their constituents using messaging, images, and other elements that appeal to our senses. These values can be associated with value, lifestyle and they can appeal directly to our taste.

When we developed the packaging for West Fork Whiskey, brand architecture was a byproduct that couldn’t be overlooked. The logo was off the table, but everything else needed to be considered. We developed a system to identify each product with as few words as possible, giving each product a name like “High Rye” or “Corn Forward,” The goal was to speak to bourbon drinkers, especially younger consumers, to introduce associated flavors and appeal to their sense of taste.

The Complex Landscape

We've talked about brand architecture as a means to represent different identities inside of a greater organization; services that reach different customers with a consistent identity, and introducing options and aiding in consumer choice. These examples, while headaches may have been had, are quite simple brand architecture examples. What happens when you have a system similar to the infamous brand architecture of Google, a company that owns roughly 232 companies, has countless product brands, and deals with a variety of ways that the brands relate to each other? In situations like this, establishing a hierarchy is crucial. But often, it's not easy. How do you address these challenges?

Very Carefully

The key to addressing a complicated brand architecture is to do it very carefully. Brand managers will need to allow their team the time to process each of the important aspects of the brand. Several of these key aspects are addressed in the above examples. Here's what we covered.

- Identities

- Audiences

- Stories

- Decisions

Identities: For every brand and its sub-brands, consider how your audience identifies with the brand. Are they a Coke drinker, or do they love Sprite? Do they love Apple as a brand and use the iPhone and Apple Music but not much else?

Audiences: Consider who you reach and whether it is a choice or a community. Buying a vehicle from Chevy offers you a choice, but a Jeep is often associated with a community. Identify when and where your product fits and who is the perfect customer within that context.

Stories: Identify how you need to communicate your brand to help your customers understand why you are the best option for them and when. Usually, this comes in the form of delivering the right message at the right time, often based on the concept of story. In most cases, segments of stories are tied to brand segments such as products, services, or programs.

Decisions: Finally, helping your customer make a decision comes from giving them cues that connect to their senses to help them self-identify where they fit or which option is best for them.

Based on all the above, I suggest you develop a hierarchy of which brands and sub-brands supersede others and when a specific brand should take center stage. And yes, an org chart on a whiteboard is usually a good place to start this process. Addressing all of these items in concert can be difficult, but doing so will definitely help your business and may help you better serve your audience, too.